Vintage: Ballyhoo, Part 1

One of the most hilarious and entertaining things about the film industry in the 1920s is how completely unbridled marketing and publicity were at the time. Today, movie marketing has fallen into familiar patterns. X months before release, we get a teaser trailer. Y months later, we get a full trailer, and over the course of a few days, maybe we get different edits of the trailer that cater to different demographic groups. Toy merchandising starts Z weeks out, with toy stores and a designated fast food chain hard selling co-branded plastic junk. It's familiar. It's boring. Not so, the advertising practices of the old days.

In the 1920s, there were no familiar patterns. The movies were still new, and businesses were less hampered by advertising laws. Studios and exhibitors could be innovative -- in fact, they had to be innovative -- to get the word out.

Interestingly, the onus of advertising was mostly on the theater owner to sell movies to the public. Today, when movies almost always open nationwide the same day, the burden falls on the studio to advertise. But way back, movies didn't open everywhere all at once, and theater owners had to make more independent decisions about what to project in their houses. The burden was on them to get the word out, and they pulled out all the stops to do it.

As this first scan from the 1929 Film Daily Yearbook indicates, the book includes a very long list of ideas for marketing stunts that theater owners can employ to sell tickets. There are some 22 pages of marketing stunts, sorted categorically, and we're going to go through every last one, a few pages at a time, because this material is just priceless. In case you're not interested in reading all this material, I've marked the most interesting stunts in red. The important thing to remember is that each of these stunts was actually used successfully by an exhibitor.

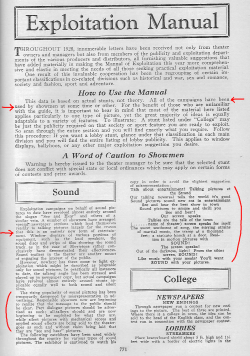

And already, filmgoers have caught on to shady advertising practices. Sound is rocking the nation, and exhibitors are desperate to sell sound, because that's what gets people in the door. The problem is, most films made in 1928 were still silent. Of the early sound films, most were "partial" sound, meaning, intuitively, part of the movie was silent and part was sound. Music was easier to record than speech, so some movies had prerecorded scores and sound effects (as opposed to musicians playing live in the theaters) but no spoken dialogue. Anyway, early on, as exhibition was still finding its way, theater owners advertised "see and hear" pictures, "all talking" pictures, and so on, in some cases when the films were not quite "all" talking. This problem fixed itself pretty quickly, though, because the sound revolution in America would be pretty much complete in another year, and silents would be a thing of the past. The mere fact of sound would very soon no longer be enough to get patrons in the door. But for now, the novelty was all the rage.

I absolutely love the sample advertising copy, by the way. I mean, I just don't know a greater advertising line than, "Like music with your meals? You'll want SOUND with your pictures."

A lot of old advertising, like the copy here, reads like literate AOL kids. They spell and capitalize and punctuate, but they're still hype machines stuck on exclamation marks and shouting and (as seen in this earlier Vintage post) boldface and underlines. Today, the fashion is for much shorter ad copy. If sound came along today, we'd come up with a catchphrase and call it a day. "Hear the difference." In 1929, if you didn't have at least five catchphrases, some capitalized buzzwords, and several exclamation marks, you just weren't with it.

Anyway, here we have the first set of marketing stunts, these designed for movies with a college theme, and at the end of this last page, we start the "Juvenile" section that we'll continue next time. As you can see, most of these stunts are about appealing to college kids and "exploiting" the college scene. The stunts are as enlightening about how much the college scene has changed in 80 years as movie marketing has.

My favorites are denoted in red. The Drawing Contest is great for the last sentence. If your art stinks -- and how one makes that determination, I do not know -- then you can enter a special tracing contest. Brilliant.

The College Beauties stunt is hilarious, but hard to comment on. It's easy to say that it was more common and socially acceptable to iconify beautiful women and "exploit" imagery of beautiful women for commercial or simply frivolous purposes. But we still have pageants, and even elsewhere we still exploit the same imagery in virtually every corner of the media. We're just a little less forthcoming about it. Maybe a lipstick ad is the result of some company's private search to hire the most beautiful woman they can find. That's a contest of a sort, but we don't call it that, and in any case the woman is only beautiful because she uses Brand X lipstick, right? But there's something refreshingly honest about a newspaper printing some photographs and saying, "Hey! These are some hot chicks! So go see this unrelated movie!"

Note the very careful wording. A sign announces that the movie's star will select the six prettiest girls. The newspaper will publish the winning photographs. Does that mean the six prettiest girls in Bunktown, Indiana, would not necessarily be personally selected by Douglas Fairbanks but in fact selected by the grungy theater owner? Who knows. The book claims that the stunt was actually employed at least once (and potentially many times), but it's careful not to claim that the star was the real judge, and it's careful not to suggest to exhibitors that they pull off a scam.

My third and final favorite stunt for this week speaks for itself. It's the Ukulele Contest. Let me repeat that again. It's a Ukulele Contest. The write-up inexplicably neglects to mention how you use a ukulele contest to sell a movie, because there is no mention of how the movie ties in. Maybe the prizes are free tickets, or maybe the contest and the special luncheon are "brought to you by" whatever theater, showing whatever movie.

No matter. The point is, oh how I long for the day I can snag a free ticket to Spider-Man 3 by winning a ukulele contest.

|