Vintage: Ads For Artists, Part 1

The Film Daily Yearbook was about 50% listings of movies and credits and theaters and statistics, 10% editorials, and 40% ads. Some of the ads were for industry services, which we'll cover in future weeks, but most of them were for artists and craftsman in the industry: actors, directors, cinematographers, and "scenarists," as the writers were called. Here are a few of these ads from the 1928 edition and some of the thoughts they inspired.

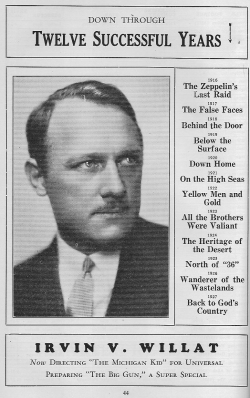

One of the astonishing things about browsing these ads is just how few names and titles are familiar. As I said earlier, I wouldn't be surprised if 90% of all silent films are lost. Since writing that, I found confirmation that the figure is estimated at 80-90%.

If your interest in movies is not completely casual and rooted in the present day, you probably at least recognize many titles from random lists of noteworthy films. And if you're a scholar or an enthusiast, maybe it's unusual to see a list of movies of some sort where you don't recognize the majority.

One of the things that makes silent films so fascinating is they were always doing stuff like this. Today, we're too safety-conscious to be any fun, and computers give us the images we need. But in the 1910s and 1920s, if you wanted to shoot a movie where a couple of planes fly close together and a guy jumps from one to the other, you just did it. And if the planes crashed, well, all it took was a rewrite. You weren't recording sound, so any dialogue changes and most story changes could happen in post-production anyway.

Here's another unfamiliar name and a list of unfamiliar credits. I recognize the title "The Great Gatsby," of course, but not from this film adaptation, which is lost, along with most of the rest of her work. Her most prominent credit seems to be for the 1931 film A Free Soul, made well after this ad was published. A Free Soul made a star out of Clark Gable, seemingly because he slaps around Norma Shearer, one of the biggest stars of the day. Gable had been working as an extra for seven years before landing a contract with MGM that gave him this role and others that launched him to the top of the A-list of leading men.

The term "scenarist" (or "scenario writer") seems to be the favored term of the day. It is still used today, but "screenwriter" and even "scriptwriter" are far more common. While the terms are interchangeable, a certain amount of distinction makes sense. Writing for silent movies is a much different sort of craft as writing for sound. Silent movies did, of course, have dialogue, which was displayed on title cards, but a larger percentage of the work a silent film writer must do is create the scenario, the story, rather than the words used to convey it.

Well here's a guy I do know, for the role featured here. Most of the photographs in the ads for actors and actresses show them out of character, but Sunrise was such a defining film that, I guess, it made sense to advertise O'Brien with a shot of his scruffy, haunted character. The film is visually astonishing and strikes such a compelling tone that it is not easily forgotten. Its merit was recognized in its day, as it won the Academy Award for Best Unique or Artistic Production, the first and only time that category was recognized, and the film continues to be honored today. In the 2002 Sight & Sound Poll of the best movies ever made, for example, Sunrise ranked #7. While the film's dramatic visual style garners the most attention, much of the film's success is owed to George O'Brien's unforgettable portrayal of a man who is torn between conflicting passions. We'll be talking more about Sunrise on the podcast around the end of next month.

Anyway, here's another example of evolving terminology. The word "characterization," to refer to what we would call a role or performance, appears pervasively throughout the film literature of the 1920s. It's an essentially unused definition today. If we say a movie had bad "characterization," we probably mean that the film's characters were not well defined by the screenplay. In the silent era, the comment would be more likely interpreted as a criticism of the acting. Again, the shift in terminology may be related to the difference between silent and sound films. Character definition owes more to the acting in silent films, whereas in sound films the writing plays a larger role.

Here's another ad with a Sunrise credit. Karl Struss was a top cinematographer in the 1920s, and his career was only just beginning. By the time he retired in 1959, he had clocked up some 140 film credits. Besides the spectacularly photographed Sunrise and Ben-Hur (the original silent version) mentioned here, he would go on to photograph Charlie Chaplin's The Great Dictator (1940) and Limelight (1952), spy thrillers like Journey Into Fear (1943), and horror thrillers like The Fly (1958).

This page caught my eye, however, because of the amusing discrepancy between the complexity of the two ads on this page. A surprising number of the ads consist of nothing but a name on an otherwise blank page. But if I had been Roland Drew, I wouldn't have been sure which was worse: having a mostly blank ad right next to Struss' more dazzling ad, or having the entire content of my ad define me by the fact that I once played opposite a bigger star.

|